This documentation is, just like Runtime, still a work in progress. While it is technically done, I have no doubts that people will be able to find problems with it. If you notice something is awry, don't hesitate to create an issue on the runtime-site github page.

| Getting started |

|

To get started, you should install Runtime. Links and instructions are available here.

First, you should try seeing if you can get into the Runtime environment. Assuming you have it properly

installed, you can simply run

Runtime runs code in two seperate ways, either in the live interpreter, which is what you're looking at here,

or it can directly run files, in which there will be no pretty visuals. You can also run files directly in the live

interpreter using the |

| Objects and values |

|

This guide is written under the assumption that you have atleast a cursory level understanding of programming, however you might be able to follow along even if you don't. Everything in Runtime is either object or value. This makes learning the workings of the language extremely simple, in exchange for making the process of actually writing code quite a bit harder.

Object and Print are both functions.

However, in Runtime, functions are objects.

This leaves us with "Hello world" and str, the former of which is a literal, and

the latter a variable, which also happens to be an object.

This might leave you with some questions. If str is an object, then what are values?

|

| Members |

|

Like you would assume, objects can have members. For example, in the previous snippet of code, str had an unnamed member with the value of "Hello world". You can access members using the accession operator - Object(str "Hello") # Commas are completely optional in Runtime. You can add them if you feel they help code readability Print(str-0) # This prints HelloHere str was assigned the value, by default, at it's 0th index. You can think of objects as arrays.

However, you can also think of objects as dictionaries, since you can also assign members via a string key. Object(str) Assign(str, "msg", "Greetings!") Print(str-"msg") # This prints Greetings! Print(str-0) # This also prints GreetingsEvery member with a string key also has an int key, however this is not necessarily true the other way around. |

| Creating and manipulating objects |

|

Objects can be created simply by referring to them int # This creates an empty object called intIf you want to give objects members, this can be done using either the Object()

or Assign() functions.

TODO: object doesnt evaluate, assign does

|

| Evaluation |

|

Look at the following snippet of code

Object(i Input()) # Assign user input to the variable i

Print("Hello")

Print(i)

How would you assume the control flow would work?

The answer is lazy-evaluation, or as I call it in Runtime, questionable-evaluation. Lazy-evaluation means that values are only evaluated when needed. For exaple, in Haskell you may assign the numbers 0-infinity to an array. While in most languages this would be impossible, Haskell allows this because it will only evaluate the numbers when you ask it to.

This is also how it works in Runtime. In the code snippet above, while i is assigned the value of However if you're a Haskell aficionado, you may see a problem with this: Runtime is not purely functional, which means functions can have side effects. This is where the "questionable" part comes in. It is entirely possible, that the return value of a function has changed in the time it took between assigning it to a variable and actually evaluating it. This is simply one of the things you will have to keep in mind when writing code in Runtime. |

| A quirk of evaluation |

|

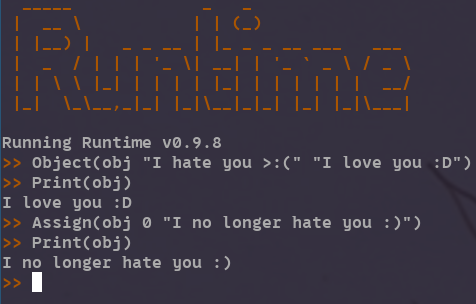

In order to understand evaluation fully, you will need to be aware of the specific mechanisms behind how it works. In the last chapter we went over how an object with a single value is evaluated. However what if an object has multiple members? In that case the member which was lasted assigned to will be evaluated.

|

| Functions |

|

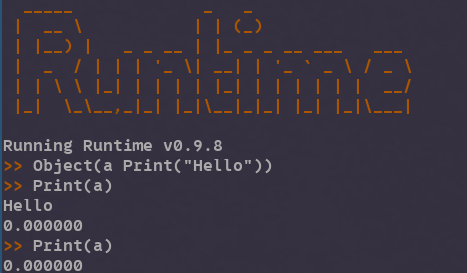

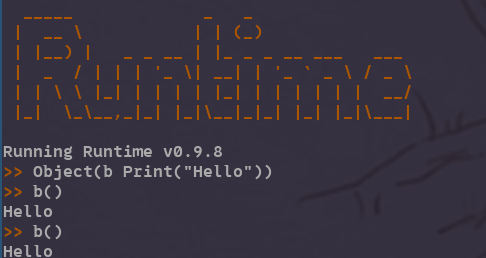

In the last chapters, we went over evaluation. However in order for Runtime to be langauge that can actually be used for anything, there needs to be a second mechanism for evaluating objects. That mechanism is calling . Every object can be both evaluated and called, and in principle they are not so different from eachother. While evaluating an object will... evaluate it's last assigned to member, calling an object will evaluate all of an objects members in order of assignment, before returning the last one.

This, however, is where things start to get difficult. While the basic concept of functions is what was just described,

there are quite a lot of quirks in the implementation which make things harder. For example, evaluating an object or its value

will write the objects value to memory, whereas calling it will not. Heres an example to try to help you understand.

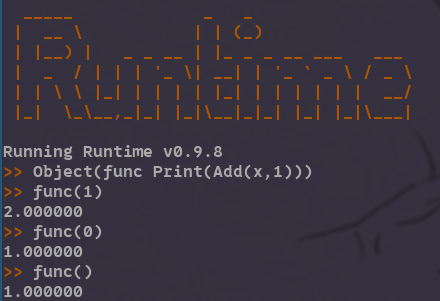

The last image should give you decent idea of how functions work. You create an object with a series of object calls, then you call that object, which results in all of its members being evaluated. Now we must move on to arguments/parameters.

Here is a simple function which takes a single number as an parameter and prints its following digit.

|

| References and values |

|

Objects are always passed by reference, and values are always passed by value.

Object(one, 1) Object(value, one-0) # Passed the value of one Object(reference, one) # Passed a reference to one Assign(one, 0, 2) Print(value) # Will print 1 Print(reference) # Will print 2This is another case where the workings of evaluation will be prone to mess things up. |

| Quick overview of standard library | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Congratulations! You've made it to the end of the documentation. In theory, you should now be able to write functional Runtime code, although in practice it will of course take some time before you're able to fully grasp the language. This section will be a quick overview of some of the most useful functions that come with Runtime. A full reference of all Runtime objects can be found here.

|

| About Runtime |

|

Who?

What? Why? |

| Documentation |

|

Installation

Getting started Reference |

| Download |

|

Binaries

Source |

| Contact |

|

Github

Other socials |